Is 'systems generated trauma' a real thing for parents of disabled children, or are we being melodramatic?

A personal account of navigating public services for disabled children, and the unsettling accuracy of the new Cerebra report.

It sounds awfully dramatic doesn’t it?

‘Systems generated trauma’.

When the charity Cerebra published their report last week and used that phrase – systems generated trauma – to describe the experiences of parents of disabled children in asking for help and engaging with the education, health and social care system – I felt the oddest mix of relief and exposure. Relief that seasoned academics had committed pen to paper on an issue I know to be true. And exposure because the very black and whiteness of it, the bold terminology, the big, heavy, clinical sound of those words made me second guess myself.

Is it really trauma? Am I being melodramatic?

Let me take you back, for a moment, to 2011, when my family and I first entered the ‘system’. I keep wanting, by the way, to put ‘system’ in quotation marks because the word doesn’t quite capture the reality of it. The word system suggests something coherent or joined-up, it feels way too neat for something so inherently messy. If I write system with no quotation marks it feels as if it is a single, functioning, recognisable thing out there that we are interacting with. But in my experience – and the experiences described in the report, the ‘system’ isn’t a system at all. It’s a collection of disconnected departments, contradictory advice, outdated databases, exhausted professionals, and processes capable of making catastrophic mistakes.

So, back to 2011. I want to say it is September, a too warm late summer day in London, and I am sitting in a windowless paediatrician’s office in the Evelina Children’s Hospital, my six month old baby lying on the examination table on his front in nothing but a vest and nappy. A typical six-month old would be pushing up and moving themselves around by now, propping on their forearms, sitting up, reaching for things, lurching and wobbling around the place with curiosity.

But my baby lies there, perfectly still.

His face is turned to one side, his cheek pressed against the paper roll. His arms and legs are curled up underneath him. He doesn’t try to lift his head.

The paediatrician pokes and prods my son and asks about milestones. Makes notes. His silence lengthens and I feel the heat rising in my chest. When he lifts my son back into my arms, he melts against me like warm dough, not a hint of the wriggling or twisting you see in other babies his age. I kiss his head. He is perfect. And something is wrong.

Eventually the paediatrician clears his throat and begins that now familiar medical dance, the one where the professional knows more than they are prepared to say out loud.

“So, we’ll run some genetic tests,” he tells me. “Just to rule things out”.

He doesn’t say what things.

“And I’ll refer him to physiotherapy. It may help with… getting him moving.”

“For the longer term, he may just need a little extra help when he gets to school. Or he might go to a special school. It’s too early to say.”

I wait for the next part – some hit of a plan, a diagnostic pathway, perhaps some reassurance that there is some identifiable source to turn to, someone who will help guide us, but it does not come. Already there is a sense that we are largely on our own.

Fourteen years later, with the retrospective clarity that only living and experiencing can give you, I can see that this was the the non-beginning of support, the moment we slipped into the gaps between health, early years support, education and disabled children’s social care without anyone really noticing. We had no idea of the long road ahead, or how much of it we would be expected to fight for. We didn’t know, standing there with our six-month old and a handful of referrals, that we were stepping into a world so opaque that half the time you can’t even tell which door you’re supposed to be knocking on, and where the people on the inside can seldom agree on whose job it is to help.

Looking back now, I can see that this was our first encounter with what Cerebra’s report identifies so clearly. Not one system – because there is no single system – but the multiple services that do not connect, collaborate or communicate, and the cumulative harm that this disconnection can create. That appointment was just the beginning of a long (lifelong) exposure to the fragmented structures that shape so much of the life experience of parents with disabled children.

And even now, fourteen years in, with all the benefit of experience and the knowledge we have amassed, if anything, the loose threads have multiplied. Wheelchair services have sent us to the back of the referral queue again. Continence services seem to have evaporated. The home adaptations team has us caught in a kind of administrative purgatory. And my son still has no diagnosis. The geneticist retired at just the moment we thought we might be getting somewhere, leaving a tiny piece of my son’s upper arm tissue in a specialist lab in Italy, suspended in scientific limbo. Does anyone know what became of the test? Would anyone even tell us if they did?

This is what fragmented systems do. They leave you feeling unseen and unheard, forever nudging at closed doors, forever chasing things up, forever wondering if the things that matter deeply to you have simply slipped off someone else’s desk. There’s a heavy price to pay for holding together a life that the systems around you treat as optional. Forgettable.

I think the first time I realised this was not a partnership, that there was no real empathy, no trust, no sense of shared accountability, was at a ‘Team Around The Child’ meeting (which still makes me laugh, because there was nothing I would recognise as a team, and certainly nothing around the child). Six professionals sat around in my living room drinking the tea I’d made, while the lead coordinator tapped everything I said into her laptop as though I was giving evidence.

How much physio did I do with him each day? What developmental activities was I setting up? Which appointments I had taken him to? How was I supporting his feeding? What groups was I taking him to?

Not one of them asked how we were coping, whether any of this was remotely sustainable, or what they individually could do to help. And when they asked the ritual closing question What one thing would make things better? I said the honest thing: respite. Because childcare, either via a formal nursery setting, or the informal kind mothers reciprocally offer for each other, wasn’t available for a child with the degree of developmental disability my son has.

The response was a firm reminder that I had chosen to make my own life harder by being a working mother as well as a parent carer. As if earning a living disqualified me from needing support, and that my growing exhaustion was a lifestyle choice, not the by-product of systems not doing the jobs they exist to do. (I have also not forgotten that every one of those six professionals was also a working mother.)

There are darker chapters I won’t go into here. What I will say is this. Over the years of navigating these systems on behalf of not just my son, but in more recent years my daughter too, the systems don’t just fail to support us in their very predictable ways, at times they actively frighten us too.

We’ve had decisions made about us without us, records falsified and accessed without consent, assumptions treated as fact. We’ve lived through a hospital situation where our attempts to advocate for our child’s safety were reframed as something else entirely. We’ve also endured the kind of experience no responsible, loving parent ever forgets. The one that tells you, over the speaker phone in the car on the way to a health care planning meeting where you need to be composed and articulate, that a child protection investigation is on the cards, off the back of what was then discovered to be a huge misunderstanding between professionals, and a lack of neurodiversity experience, too.

Once you’ve been on the receiving end of these systems at their worst while knowing that you are absolutely doing your best, you never walk into a room of professionals the same way again. The trust is gone. The fear lives just under the skin.

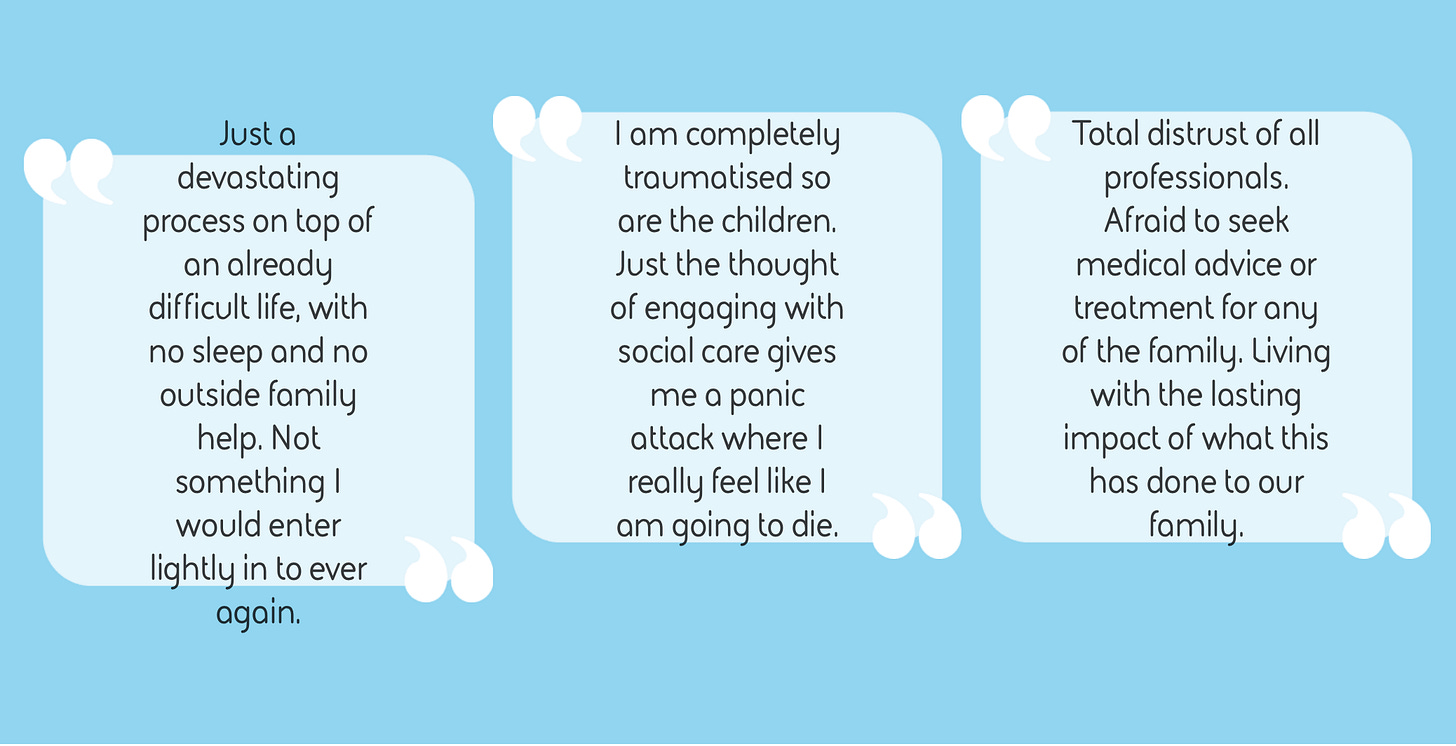

Back in 2021 I wrote a piece listing the hidden sources of stress for families like ours. Hundreds of parent carers responded to say they’d lived the same thing, that dealing with the systems wrapped around our children’s disabilities created the greatest pressure in our lives. At the time I worried I was being dramatic, or that I’d simply had a particularly bad run. But now this has been solidified in Cerebra’s national research, the stark finding that the most damaging traumas many families experience result from dysfunctional public systems, the recognition is both validating and devastating at the same time.

That same year I even had an informal conversation with a professional contact, who is a senior barrister in the SEND field – not because I was gearing up for a fight, but because I genuinely didn’t understand what was happening to us. I needed someone outside the situation to make sense of it, to get some reassurance. What I received instead was a kind and gently worded response that told me there were potential grounds for a Human Rights Act claim in relation to both the actions and inactions of the local authority and NHS bodies. Hearing it framed that way was disorientating and we didn’t pursue legal action in the end. Not because we felt he was wrong, but because we simply didn’t have the capacity to take on something so consuming, knowing that we will have to engage with these systems for life. At a certain point, everything you have goes into your children and keeping your family steady. And that is part of the bind. The systems that create the harm also leave you too depleted to challenge it.

Along the way, though, I have cobbled together ways of coping.

At first, I fought. Hard. I challenged decisions, asked questions, pointed out contradictions, tried to make people see the injustice of what was happening. Mostly this was exhausting and fruitless, like shouting into a vacuum.

Fear and exhaustion have a way of mutating a person. I haven’t always been my best self in situations where I have been terrified and not listened to. And after years of that, I retreated. Hid from the world. Cut myself off from friends. Stopped trusting my own instincts. None of this, I recommend.

But throughout all of that, in our small world, we have held on to each other tightly as a family. And that has seen us through some unimaginably hard times.

During one of the most difficult periods of our lives, a ward manager told us in a care planning meeting for our child that she and her team admired the way our family cared for one another, and how engaged we were as parents in what was an impossibly challenging recovery process. She was ballsy enough to commit this opinion to permanent record too and I have kept the letter that spells out in black and white that at least one health care team in the ‘system’ believed in us at a time when other professionals hadn’t. I hope she always remembers the difference her support made to us and our ability to carry on.

One thing I have learned in recent years is to maintain a healthy, protective distance from public services and to take back control where I can. Everything by email. One dedicated inbox. Limit meetings. Take a month off twice a year from engaging at all. Sometimes they respect these boundaries and sometimes they don’t. And the invisible wounds still remain – the fact I now hold back from challenging services when they fail us, because of what it does to my nervous system. The way a single phone call can trigger fight, flight, freeze or fawn. Flashbacks. Shouting in my sleep. I am not the same person I was. I can only manage one battle at a time now, no more.

And yet I know there are people inside these systems who want to do better. We’ve experienced genuine excellence along the way, too. My son’s special school, a handful of occupational therapists, and emergency healthcare teams who have met us with real humanity. But that doesn’t deny that there is systemic failure here, that something is deficient at the level of culture. A better system, in my view, would be one that fosters a culture of service, one built on partnership rather than paternalism. Small steps could make a difference – consistency, communication, humility, and an understanding that families like ours are experts in our own lives.

If I had to offer one tool to others navigating this – carers and practitioners – it would be this: build your stamina. Build your own personal systems of survival to withstand what the ‘system’ demands of you. DBT saved me. Weight training saved me again. These are both evidence-based ways of treating trauma that I would recommend to anyone. And alongside that, maintaining a detailed record of every interaction, and talking about things with other people, keeps me functioning. It’s astonishing how easily this stuff can make you question your own memory, your own judgement, your own sanity. You need anchors to hold you steady.

These anchors don’t change the systems but they do give some solidity to the ground underneath my feet. Enough clarity to stay connected to myself, and enough strength to meet whatever comes without losing who I am.

The Cerebra report puts language to things many parent carers have carried alone for years, and there’s also some steadiness to be found in that. It doesn’t fix anything, and I am yet to see a national newspaper or a politician pick this up and run with it in the way it deserves, because our experiences as parent carers are not unique, we are perhaps the canaries in the coal mine for a whole host of systemic, cultural issues in our public services today. But it does offer something – a way of saying this is real, it’s not just you, and you are not imagining the weight of it all.